Should Ultra-processed Food Be a Public Health Target?

Thoughts on the Twinkie, how we categorize food, and R.F.K., Jr.

Most people I know are still stunned and grieving from the election, and revolted by the people being named to leadership jobs. If we’re thinking of the future, it’s mainly about how to resist.

But at some point, we should also start thinking about how to find opportunities in the crisis. That thought led me to…the Twinkie.

Nearly everyone would agree that the Twinkie is bad for your health. But why, exactly?

Here’s its Nutrition Facts panel:

If you’re trained in nutrition or medicine, you’re likely to say the Twinkie is bad for you because it’s loaded with added sugar, sodium, and saturated fat. Or because it doesn’t have any ingredients that we need more of: no vegetables, fruits, fiber, whole grains, or potassium.

But plenty of people in this country will instead say the Twinkie is bad for you because it is laced with chemicals with unpronounceable names, like sodium stearoyl lactylate, and food dyes like Yellow 5 and Red 40. Earlier this week, I spoke about this to Mike Jacobson, who ran the Center for Science in Public Interest for decades, and who coined the phrase “junk food”. His experience is that Americans as a group are much more worried about the chemical additives in food than they are about the main ingredients.

That worry has spawned today’s food influencers who make a living criticizing the chemical additives in food. They’re gaining huge followings by tapping into the intuitive belief that natural equals healthy and artificial equals unhealthy.

If you want a very simple rule to guide your eating, natural vs. artificial isn’t a terrible one. It’s probably better to eat random plants than swallow random chemicals from your kids’ chemistry set. But, even leaving aside the knotty question of how to define “natural”, the natural vs. artificial rule can sometimes lead you dangerously astray.

Plenty of plants are both natural and toxic. More important, ingredients like salt and sugar, which most people consider “natural”, are very unhealthy when consumed in the amounts that Americans do. As Mike reminded me, the dose makes the poison.

The sodium in salt is a driving force behind hypertension, which afflicts nearly half of U.S. adults. Excess sodium is estimated to kill about 50,000 Americans per year. Added sugar is linked to weight gain; beverages full of sugar are linked to diabetes and cardiovascular disease. The evidence we have says that these, not sodium stearoyl lactate or Red 40, are what makes the Twinkie dangerous.

The food companies know that their customers equate natural with healthy, so they take every opportunity to present their foods as “natural”. They may rebrand their ingredients as “sea salt” or “organic maple sugar”. Even the website where I found the Twinkie nutrition facts panel tells us helpfully that the Twinkie has “No artificial sweeteners” and “No artificial preservatives”.

Now an increasing number of public health people are taking a new tack, saying that the Twinkie is unhealthy because it is ultra-processed.

What is ultra-processed food, anyway?

(If you already know about ultra-processed food, you can skip to the next subheading.)

The idea of categorizing food based on how much processing was involved in making it came from Brazilian epidemiologist Carlos Monteiro in 2009.

In what is now called the Nova system, he grouped food in four categories:

Group 1 are unprocessed or minimally processed foods, like fruits, vegetables, meat, and milk;

Group 2 are ingredients extracted from Group 1 foods like oils, sugar, and salt;

Group 3 are processed foods made by combining Group 1 and Group 2 ingredients, like canned vegetables with added salt or canned fruit with added sugar; and

Group 4 are “ultra-processed” foods, which are made mostly or entirely from Group 2 ingredients and additives, and which require a lot of processing, like sugar-sweetened beverages, breakfast cereals, hamburgers, chicken nuggets, and Twinkies.

The Nova system has practical and nutritional problems. The definitions use vague words like “mostly”, “in many cases”, and “normally”. And some of the categorization doesn’t seem to make nutritional sense. For example, plain potato chips are not considered ultra-processed. Whole-grain bread, which I think we want to encourage, is considered ultra-processed. And some canned beans are counted as ultra-processed while others are not.

But any system to classify food has problems like these. We now know that the old approach of grouping food by how much of it was fat, carbohydrate, and protein was definitely unhelpful. And today I doubt you can get half-dozen nutritionists to agree on whether foods like dried fruit, tuna canned with salt, tortilla chips, and whole-wheat crackers should be labeled as healthy or unhealthy.

Despite the problems, research is showing that the Nova system is a pretty darn good way to identify unhealthy foods. Observational studies are showing that people who eat more ultra-processed foods gain more weight and are more likely to develop type 2 diabetes (here and here), heart disease and stroke.

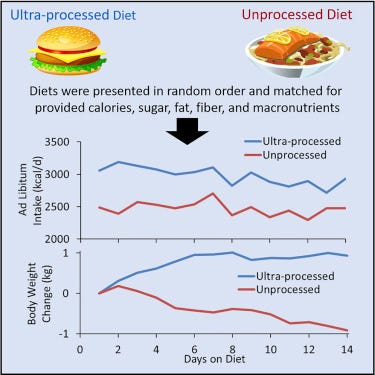

And one astonishing intervention study, in which 20 people were locked in a food laboratory, found that when they were given ultra-processed foods they ate about 500 more calories per day than they did when given unprocessed foods. During the unprocessed phase they lost about two pounds, and during the ultra-processed phase they gained about two pounds. In just two weeks!

The study has been criticized because it lasted such a short time. But when you combine it with the years-long observation studies, the evidence that ultra-processed food causes obesity and chronic disease looks very strong.

The food lab study’s authors did something I have never seen before: they included a supplement to their paper with pictures of the foods that they gave study participants. Here’s an example of an ultra-processed meal and an unprocessed meal.

I was struck that the ultraprocessed meal doesn’t look all that junky. It’s not all Twinkies. It looks like a meal you might get at Shoney’s or a Picadilly cafeteria. It looks like…well, the typical American diet.

Sure enough, the American diet is full of ultra-processed foods – about 58% of calories, in fact.

How can we use the ultra-processed food designation?

The categorization of ultra-processed food is now looking useful because: 1) it now has a strong scientific basis, and 2) unlike other ways we’ve used to categorize food, it aligns with the natural vs. artificial categorization that people intuitively trust. It even aligns with the conspiracy theory theme of our times. After all, it is true that the big food companies, often working together, influence government to push processed food that is killing us. (Marion Nestle - one food influencer that you ought to follow - has been documenting this for years.)

Maybe the ultra-processed label is a way to get traction where we’ve been spinning our wheels. Despite the enormous publicity about the obesity epidemic, consumption of junk food has barely budged in the past two decades. And an initiative by public health departments to reduce salt and sugar in processed food, after some small initial gains, has mostly stalled for lack of political oomph.

Just talking about food as ultra-processed by itself is unlikely to work, though. Everyone already knows Twinkies are bad. But maybe the ultra-processed designation can be used in food policy. For example, the school food program could adopt rules that limit ultra-processed food. Or it could be tied to food labeling, or government food procurement rules.

Other countries are beginning to work the ultra-processed concept into food policies. Brazil’s national dietary guidelines now tell people to avoid ultra-processed foods. Following that, Rio de Janeiro passed a law to prohibit ultra-processed foods in schools.

Is there a political opening for this kind of thing in the U.S.? It’s not taking hold yet. Marion Nestle is calling foul that the upcoming 2025 Dietary Guidelines for Americans will not even mention ultra-processed foods.

Here’s where our current political crisis comes in. Robert Kennedy, Jr. is making loud noises about chronic diseases and corporate influence on food policy. And he is highlighting ultra-processed food.

I’m sure Kennedy doesn’t truly care about junk food, any more than he truly cares about the environment, autism, vaccines, ivermectin, fluoridation, or children’s health in general. He’s just putting up sails to catch the political winds.

But his talking about ultra-processed food is drawing new attention to the junk food problem, even on the political right. Maybe we can further boost that attention to get the concept worked into food policy. If so, that could be a big win for health.

That’s not even close to a substitute for a sane President or a sound democracy, of course. But it’s a little something positive to think about in tough times.