I follow the sport of track and field like basketball fans follow the NBA. I never expected that that hobby would overlap with my day job in public health, though. Until it did.

One of my favorite athletes is Allyson Felix, a once-in-a-generation talent who earned a combined 31 Olympic and World Championship medals, including seven Olympic golds. When Felix was 7 months pregnant with her first child, she developed severe pre-eclampsia, requiring an emergency c-section. Her daughter, born at 3½ pounds, spent a month in the neonatal intensive care unit, and Felix had her own medical complications, but the two survived.

Felix’s teammate Tori Bowie was not so fortunate. Bowie, with several Olympic and World Championship medals of her own, was on the same gold medal-winning 4 x 100m relay team as Felix in the 2016 Olympics.

Tragically, Bowie was found dead at home eight months into her pregnancy, with the cause suspected to be complications of pre-eclampsia.

Later, I ran across data showing steady year-after-year increases in pre-eclampsia in the District of Columbia. That’s when I realized that these star athletes were victims of a much bigger problem.

The surge in hypertension in pregnancy

Women are diagnosed with pre-eclampsia if during pregnancy they develop hypertension (high blood pressure) and damage to their kidneys, seen as protein in the urine. If they develop high blood pressure without the kidney problems, their condition is called gestational hypertension. Pre-eclampsia and gestational hypertension together are labelled pregnancy-associated hypertension. And some women begin their pregnancies with high blood pressure, called just chronic hypertension. All of these conditions fall in the general category of hypertension in pregnancy.

CDC compiles data about all women giving birth in the U.S., using information from birth certificates. The birth certificate files don’t have flags for pre-eclampsia, but they do for pregnancy-associated hypertension and for chronic hypertension. When I first looked at national trends in these, I was stunned.

These conditions have risen for at least the past 30 years, and they have more than doubled just since 2012. The surge can’t be explained by improved reporting of these conditions on birth certificates, because studies using other, more detailed data sources have found similar increases (here and here). The rising trend may have begun as early as the 1980s.

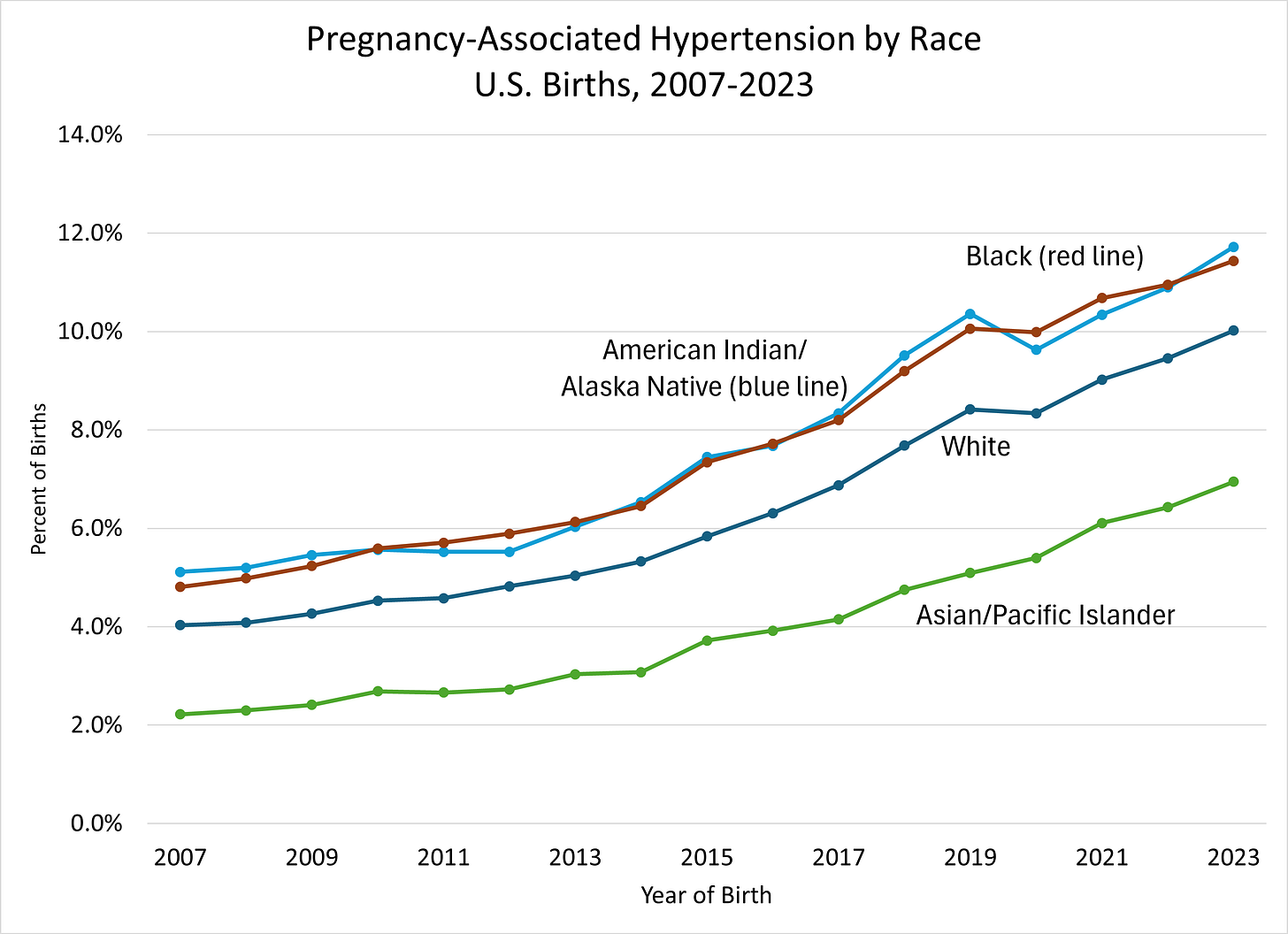

Black women are at much higher risk of pre-eclampsia, as are American Indian/Native American women, but increases in pregnancy-associated hypertension have occurred in women of all races.

Why does it matter?

High blood pressure in anyone is a marker that something is going wrong with the cardiovascular system. Its consequences are severe, including heart attacks, strokes, and kidney failure. When pregnant women have hypertension, both they and their infants are at serious risk.

Babies of mothers with hypertension in pregnancy are more likely to be born preterm and with low birth weight, and more likely to die in the first year. The survivors are more likely to have their own cardiovascular risks as adolescents.

Mothers with hypertension are more likely to die from pregnancy, and to develop heart disease or stroke years later.

With the increases in hypertension in pregnancy, there have been population-wide increases in severe maternal morbidity – problems like heart disease, kidney diseases, and bleeding during pregnancy or around the time of delivery. And after at least 50 years of dramatic improvements, since about 1990 we have seen increases in deaths from pregnancy (even if you ignore the COVID-related spike in 2020-21):

There are big racial disparities in these deaths, with Black, American Indian/Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander women at much higher risk. Here are pregnancy-related mortality rates by race for the three years before COVID:

But the rise in pregnancy-related mortality, like the rise in hypertension in pregnancy, has occurred in all race groups (here and here).

What’s causing the increase?

A few conditions are known to put women at greater risk of pre-eclampsia. Most of these are not under women’s control, though, and most are not changing much, so they can’t explain the surge. They include having a first pregnancy, being a relatively older (30s or beyond) mom, and having a family member with pre-eclampsia.

Obesity is a major risk factor for hypertension and for pre-eclampsia, and one that has skyrocketed in the past 30 years. Before I dug into this topic, I guessed that the obesity epidemic would explain any in pregnancy-related hypertension. I was wrong. The birth certificate data show increases in women at all weight levels:

More generally, having any early markers for cardiovascular problems before pregnancy begins increases the risk of pre-eclampsia. Experts have called pregnancy an “early stress test” that brings to light unrecognized problems with women’s cardiovascular systems.

As the first graph in this post shows, women are increasingly starting pregnancy with chronic hypertension. Other studies have found that they begin with less-healthy cardiovascular systems overall. Why that would be true, though, is a mystery, especially when rates of hypertension in adults as a whole have been flat for about the past 20 years.

And that can’t be the full story. It seems ludicrous to suggest that Allyson Felix and Tori Bowie – the fastest women on the planet - might have had cardiovascular problems before pregnancy.

What should we do about it?

So what should we as a nation do about this problem that is big, growing fast, and not well understood?

First, save today’s moms. Experts estimate that 60% of maternal deaths are preventable with optimal medical care. Medical quality improvement teams in hospitals across the U.S. now are working on just that.

Second, treat this problem early. The CDC has recently published guidance for health care providers on how to ensure that pregnant women with hypertension are identified early, treated correctly, and followed closely until they deliver safely.

Third, go upstream and do research on why young women increasingly have high blood pressure. Maybe it’s the same reasons most American adults do (unhealthy diets, sodium, alcohol, obesity, physical inactivity), or maybe there’s more to it.

Fourth, monitor this closely with strong data systems. Because we don’t know why hypertension in pregnancy is surging, we also don’t know what will happen next, or whether our attempts to solve this problem will work. We’ll never know unless we measure it.

Who will lead our response?

Incredibly, the unit at CDC charged with solving this problem is hanging by a thread.

CDC runs the data systems that we all use to spot problems with pregnancy and birth. CDC supports the medical teams working to improve the quality of maternity care in hospitals. CDC puts out the guidance to prenatal care providers on treatment of hypertension, as well as leads a national initiative on hypertension in all adults.

CDC’s Division of Reproductive Health, which is at the center of this, was slashed in the HHS April 1 massacre, and their director was put on administrative leave. Now HHS is proposing to eliminate the unit entirely. That would mean no data, no experts, no national prevention work, no way to know if things are getting better or worse.

Don’t the moms and babies in the richest nation on earth deserve better than that?

Tom: Thank you for another important perspective on public health. Pre-eclampsia is one of the most feared conditions of what is usually viewed as an amazing biological experience. Too often, pregnancies end with maternal mortality, severe hypertension, miscarriage, or premature birth. The US has some of the highest rates of poor pregnancy outcomes of all affluent countries. But as Rose said, “There is no known biological reason why every population should not be as healthy as the best.” The trick is finding the environmental influences. In environmental epidemiology, lead, air pollution, and phthalates have all been identified as potential risk factors for pre-eclampsia. The evidence for lead is strong, but blood lead levels have declined over the past 40 years, so it doesn't explain the increase. The composition of air pollution is constantly changing and plastics, like phthalates are a possible reason for the rise you described so clearly.